“All that is constant about the California of my childhood is the rate at which it disappears.”

—Joan Didion, “Notes From a Native Daughter”

Idaho’s Treasure Valley lies in the western Snake River plain, a stretch of semi-arid land with sagebrush-covered hillsides and green river valleys. My great-great-great-grandparents homesteaded there in the early 20th century. As a child, I took rafting trips down the Payette River outside Horseshoe Bend, picked buttercup bouquets in the mountains, and helped my mom can peaches from the local farm stand.

Farming most colors my memories of the land: Idaho’s agriculture industry is the single largest contributor to the state’s economy. In 2018, Edible Idaho reported that only 20 percent of all U.S. farmland has soil of the quality comparable to the Treasure Valley. This is, as the American Farmland Trust’s Julia Freegood put it, “the crème de la crème of agricultural land.”

But farms throughout the Treasure Valley are quickly transforming into suburbs these days—the broad stretches of green turning to gray, fields morphing into cul-de-sacs and strip malls. My drives from the Boise airport to my family’s home in the northwest are increasingly punctuated by the loss of earth to asphalt.

This explosion of growth is much larger than Boise: it is part of a centuries-long transformation of farm towns and cities in the West. The boom originated in California in the last century, and these days it is transforming cities like Boise, Spokane, and Reno—places where developers reportedly can’t build homes and apartments fast enough. In 2017, an exurb of Boise called Meridian was the fifth-fastest-growing city in the United States, according to the Census Bureau. And among the top 10 states that grew from 2017 to 2018, the Census found that the top four are Western, arid states: Nevada, Utah, Idaho, and Arizona.

One report warns that by the year 2100, Idaho’s Treasure Valley “could be completely unrecognizable to the people who live there today.”

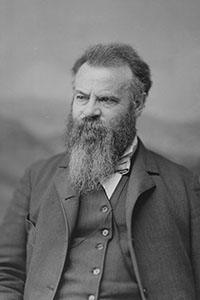

But it didn’t have to be this way. In the 19th century, a once-renowned Western explorer and scientist suggested that development of the West should include and support farmers. He warned against the sort of booming development that characterizes suburban sprawl. And I wonder whether, if we had listened to John Wesley Powell’s advice—and not mostly ignored his prophetic warnings—the Treasure Valley’s lost farmland might still exist.

***

This year marks the sesquicentennial of explorer Powell’s expedition down the Green and Colorado Rivers in 1869. Perhaps more than any other man of his time, he comprehended the limits of Western geography, and suggested that inhabiting the land would require a far different set of rhythms than those we had cultivated up to that point. He questioned the entire orthodoxy shaping the West during his age—an orthodoxy that is shaping it still.

Born in 1834, John Wesley Powell served in the Army during the Civil War, and lost his right arm at the Battle of Shiloh. After 1867, he led a series of expeditions through the West: along the Rockies and the Colorado River, through Utah farming communities and the Grand Canyon. During each of his expeditions, Powell meticulously studied the West’s topography, climate, and hydrology.

Powell’s trips throughout the West convinced him that the region’s aridity must sculpt the ways in which it was cultivated and farmed. In 1878, he published a Report on the Lands of the Arid Regions of the United States, suggesting that the watersheds of the West should determine state lines. He argued that the government should create careful surveys based on the topography of the West—very different from the crude, indifferent rectangular 160-acre parcels of federal land typically handed out to settlers—and let “farms be as irregular as they had to be to give everyone a water frontage and a patch of irrigable soil,” Wallace Stegner wrote in his 1953 study of Powell, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian. “By that system it would be possible not only to prevent monopoly of water and hence of land, but to carve the maximum number of freeholds out of any usable part of the public domain.”

Powell also argued that, rather than encouraging homesteaders to spread out in privately-owned patchworks across the land, the government ought to encourage farmers to settle in cooperative communities—akin to the Mormon settlements Powell had observed in Utah. He knew that individual initiative, labor, and money would not be sufficient to establish viable irrigation systems. Either private capital would develop (and monopolize) the water, the government would develop and distribute water, or “the people themselves, by co-operative effort such as that of the Mormons, could organize and develop in unison what was impossible for anyone singly.” Powell saw this last option as the most feasible and beneficial.

“His proposal was brilliant, and doomed,” Robert Glennon explained in Scientific American in June. “Speculators and hucksters would have seen their dreams of riches go up in flames if Congress had embraced Powell’s proposal. Instead, government surveyors in Washington, D.C., drew straight lines on a map along swaths of country they had never visited and could not imagine contained the Sierra and the Rockies.” They continued to hand out land in rectangular 160-acre parcels—and ignored the implications of the west’s aridity. Powell’s cooperative vision for the West never saw widespread realization.

“Powell’s way was a way tested by New England barn raisings and corn huskings and all the co-operative habits of country America,” Stegner wrote. “…It was recommended by logic and demanded by the hard conditions of western climate and geography. In details it could probably bear revision; in general it was inescapable. If it had been adopted it might have changed the history of a great part of the West.”

Indeed it could have. Powell biographer Donald Worster once noted that, if Powell’s plan had been accepted, “Any city—Los Angeles, for example—would have had to deal with these local watershed groups and meet their terms” in order to use their water. Water would not have been transferred from its source across mountains, “hundreds of miles away to allow urban growth to take place,” Worster said. “L.A., if it existed at all, would have been a much, much smaller entity. Salt Lake City would be smaller. Phoenix would probably not even exist.”

In 1902, Congress passed the Reclamation Act, and one of the possibilities anticipated by Powell became reality: the government funded and built large dams throughout the Western United States to store water and foster growth. Throughout the century that followed, NPR reporter Howard Berkes notes, “Cities snapped up water rights and imported water across hundreds of miles. Small farmers were overwhelmed by urban and corporate interests.” Hundreds of thousands of people moved to the West during World War II to work in the war industries; the growth of San Diego prompted the construction of two major aqueducts along the Colorado River.

Suburbanization revolutionized urban development across the United States after World War II, sprawling in low-density clusters across the country. Joan Didion chronicled the impacts of suburbanization in California in her essay “Notes From a Native Daughter”: “Sacramento is a town which grew up on farming and discovered to its shock that land has more profitable uses,” she wrote. “…It is a town in which defense industry and its absentee owners are suddenly the most important facts; a town which has never had more people or more money, but has lost its raison d’être.”

Most Western land is still owned by the federal government: the region’s 13 states are home to 93 percent of federal land. Because of this, growth in the Mountain West and Southwest is limited to very specific pockets of private land—and many of them are places where farmers have conducted their business for centuries.

It would make sense, given the limitations of available land and the importance of agriculture to many of these states, to develop new settlements as carefully and efficiently as possible. But rather than seeking to build in a manner that preserves as much farmland as possible, we’ve instead cultivated a series of policies that subsidize its disappearance.

***

Steve Nygren grew up on a farm outside Denver, on land that had been in his family since 1860. That land is now gone, subsumed into the suburban growth that has transformed Denver over the past several decades. Much like Boise today, Denver was once a small urban area surrounded by farmland, but the city’s boom has wiped out many of its agricultural operators. Its population has grown 20 percent since 2010 alone.

Nygren moved to Atlanta. in the 1970s, and in 1991, he and his family bought a little farmhouse south of Atlanta. Only a few years later, while out on a run, Nygren saw bulldozers leveling a neighboring property. He knew he had to do something.

He started buying up the land around his farm, trying to preserve it, “but at 900 acres,” he recalls, “I realized I could not buy enough to protect this from the urban sprawl.” He remembered his childhood in Colorado: “It all disappeared, people who swear they’ll never sell change their minds.” Nygren was determined—he would not let this happen to his Georgia home.

Some states have instituted measures that only allow agricultural land to be developed if it adjoins a municipality. But this solution doesn’t change a development’s density or style: while the new sprawl is a bit slower and more incremental, it doesn’t fix the problem.

Representatives from the American Farmland Trust, meanwhile, point to the importance of agricultural easements, which preserve land for agricultural use long-term via private-party or land trust compensation.

“Idaho farmers have been scared of [agricultural easement] because they thought it would tie their hands or tie the next generation’s hands,” Ada Soil and Water Conservation District Manager Josie Erskine told Capital Press. “But we may be at a place where the next generation cannot farm without these options because land is just too valuable.”

Back in Georgia, Nygren found a different answer. When he realized buying up surrounding farmland would not be enough, he brought together 500 landowners and formed the Chattahoochee Hill Country Alliance. In 2003, they began working with the University of Georgia and state commissioners to change local zoning in favor of a program called Transfer of Development Rights (TDR).

In a TDR transaction, a developer can buy a landowner’s development rights and transfer them to a different area. The developer is thus able to build more housing units than they would be able to otherwise. The landowner benefits from the sale of their development credits, while still owning their land and retaining the right to farm it. After a TDR sale, a permanent easement is placed on that land that prevents further development.

Through the TDR program, Nygren built Serenbe, a community that preserves 70 percent of its land via permanent easements and sets aside 30 percent for mixed-use development (with a 25-acre organic farm on the outskirts of the community). Its proximity to the organic farm and surrounding countryside have justifiably deemed it an “agrihood.”

Serenbe’s developers purposely avoid the massive front lawns of suburbia, instead cultivating public green spaces and nature trails around its homes. Nygren sees the neighborhood’s mixed-use zoning, dense clusters of homes, and pedestrian-centric layout as essential to its success. But it’s also clear that he sees the preservation of surrounding countryside—the farmland which his home in Denver lost—as one of its most important achievements.

A lot of people worry that Serenbe is too planning-centric and regulation-heavy. But Nygren’s response to that rebuttal is simple: “Most things that work have a plan,” he says. The standard sprawl model is also regulation-heavy and planning-centric—but it hasn’t actually created long-term prosperity. “Statistics show that we’re sicker than we’ve ever been, our food sources are not addressing the issues, and 50 percent of the cost of any food on the market is the petroleum required for transportation,” he says. “I don’t think we can point to the way we’ve been developing as a success on any measure.”

***

An increasing number of places across America are confronting the issue of new suburbia competing with farmland. Nygren has confronted the problem in Georgia. New Jersey implemented a TDR program in 2001, while residents in Northern Virginia worry about the farms they lose every year to suburban development. This issue is nationwide, and perplexing to many.

But in the West, we must also consider the way suburbia impacts water—how it preserves or squanders the resource Powell was so concerned about even 150 years ago.

In 2002, American Rivers, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and Smart Growth America reported that suburban sprawl threatens water quality and reduces local water supply: “As the impervious surfaces that characterize sprawling development—roads, parking lots, driveways, and roofs—replace meadows and forests, rain no longer can seep into the ground to replenish our aquifers,” they noted.

This results in decreased groundwater flow into springs, less aquifer recharge, an increase in flood magnitude and severity, and severe soil erosion and sedimentation (among other things). Large suburban tracts consume “as much as 16 times more water than homes on a more traditional urban grid,” while 32 percent of residential water is used on landscaping.

In the rain-heavy east, these practices are problematic. In the West, however, the status quo can be alarming. The Western region of the United States is experiencing a historic drought at present: the Colorado River and two of its largest reservoirs—Lake Powell (named after John Wesley Powell) and Lake Mead are more than half empty. Many parts of the Mountain West have experienced decreased snowpack since the last mid-century. And many climate scientists have warned that the western United States could experience more—and longer—droughts in coming years.

Some places (California and Arizona, for instance) have urged people to use less water in their homes and to cultivate xeriscapes (landscaping which uses rocks, stones, pebbles, and desert-loving plants). But in a 2010 report on the Las Vegas Valley, the Sonoran Institute warned that “the Valley is currently meeting its water needs—but only just—and further development, along with the threat of decreased precipitation in the Colorado River basin due to climate change, threaten to overwhelm the area’s resources.” Though the valley’s conservation efforts have increased dramatically, they have been “overpowered by the rapid population growth.”

Meanwhile, in the neighboring Utah city of St. George, Outside reported last year that water usage has escalated to an outrageous degree: “Thirteen golf courses bloom green amid desert cliffs,” reporter Mark Sundeen wrote. “Capillary culs-de-sac pulse with turf. Plans are underway for a Caribbean-slash-Polynesian water park with a 900-foot lazy river, a seven-story slide, and an artificial wave pool for surfers. … [The county] guzzles more water per capita than any metro area in the Southwest.”

To meet the water needs required by such features, the state of Utah plans to access water in Lake Powell, 140 miles to the east, via “a six-foot-diameter straw… [that will] suck the water 2,000 vertical feet through five pumping stations and six hydroelectric plants, crossing the Paria River and what used to be Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument.”

Denver is also trying to figure out a supplemental water source as drought and growth threaten to exhaust its current water supply: one state Republican operative is trying to run a 22,000-acre-foot pipeline from the northern end of the San Luis Valley, over Poncha Pass, to the southern Denver metro area. It seems likely that Powell would have had some problems with these measures, which remove water far from its area of origin in order to “make the desert bloom.”

Newsha Ajami, a researcher for Stanford University’s Water in the West program, suggested in a phone interview that going forward, we need new urban neighborhoods. An estimated 70 percent of the world’s inhabitants are expected to live in cities in the near future—but 60 percent of those urban areas have not been built out yet, Ajami said. Thus, “there is an opportunity to build that 60 percent differently from the cities we have right now”: by fostering more conservative water systems, emphasizing shared spaces and dense development, improving commercial water usage, and working with farmers to conserve or replenish groundwater via their irrigation systems.

***

One of the most important challenges for today’s farmers in the West will be decreasing the gap between their land’s agricultural value and its real-estate development value. It’s not an impossible feat, but will require reforming the way many of them farm. Much like building suburbia, the modern agribusiness of farming has become a sprawling and specialized endeavor—at the scale of these enterprises, farmers’ profit is spread over a massive amount of acres. To save existing farms, some approaches could look very similar to those proposed by Nygren and New Urbanists in the built environment. Farms under threat of suburbanization should be “mixed-use” (diverse). They should be “dense,” cultivating a higher amount of profit per acre through a greater diversity of what they grow (Gabe Brown’s “stacked model” of agriculture is an interesting example of how this might work). And they should preserve as much as they produce.

Just as importantly, however, farmers are going to need to be collaborative—working with their neighbors to build sustainability and security as the world changes around them. In our time, we must reconsider Powell’s proposal of cooperative communities, along with his policy suggestions for land use based on the topography, hydrology, and the limits of particular places. Powell believed in the West, and wanted people to move there—but he wanted them to do so in a way that esteemed and respected the bounds of aridity, in a way that humbled human ambition to the contours of the rivers and streams. The ways we accomplish this will and should look different from state to state. Rather than simply building a bunch of expensive new exurban “agrihoods,” for instance, we should also revitalize and preserve existing rural towns and villages. But we do need to follow Powell’s principles of particularity, collaboration, and conservation.

American hubris has often driven us to do nonsensical things in the name of ambition or profit. But Powell suggested another way forward: a more local, regional approach, in which farmers might work together to protect their water rights, desert cities might steward resources more wisely, and Western towns might cultivate cooperation and shared trust. Perhaps in our time, we will finally take his advice.

Gracy Olmstead’s writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Weekly Standard, and elsewhere. Her forthcoming book will focus on the Idaho farming community where she grew up. This New Urbanism series was supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.