Route 11 signs south of Mount Jackson. Addison Del Mastro.

The Virginia stretch of U.S. Route 11 is America. Or at least a pretty good approximation of it, a sort of visual average of a good chunk of the nation’s landscape. The first thing to note is that Route 11 was once the major north-south road in the western half of Virginia, running roughly parallel to U.S. Route 1 further to the east. And just as Route 1 was tracked by I-95, Route 11 has been bypassed by I-81.

I drove this old highway from Winchester to Roanoke, the most populated portion of its Virginia stretch. Partly to fit the theme and partly to make such a long drive possible, I also overnighted at a midcentury family-owned motel (where, to my surprise, I was the only guest in the entire establishment). This is not a trip many people make anymore, but it reveals many insights about the history of how we build—and abandon—places.

This stretch is not a major route. It’s a sort of second-tier megalopolis, hundreds of miles from any city over 100,000 people, except for Roanoke. Route 11 passes through town after town: Winchester, Stephens City, Middletown, Strasburg, Woodstock, Toms Brook, Mauertown, Edinburg, Mount Jackson, New Market, the economically livelier and better-known trio of Harrisonburg, Staunton, and Lexington, then on to Natural Bridge, Buchanan, and Roanoke. There are many post offices and churches along here too, with names on the map, suggesting that at one time there may have been many more towns, at rail stops or once-important intersections.

One can imagine a world in which the towns along here grew enormously and became little historic districts within a sea of modern sprawl, like the transformation of Northern Virginia over the last 70 years. But most of the economic growth in this corridor since midcentury has followed I-81, gateway to the south. I-81 is also a burgeoning trucking route, lined with one massive warehouse after another. At times, I could idle my car, stand in the middle of Route 11, take a picture looking down its empty stretch, and watch the trucks zoom by just a couple hundred feet away.

♦♦♦

Route 11 is notable not just for its wealth of classic Virginia towns, but also for its highwayside sprawl, or what’s left of it. For someone interested in the built environment and the history and patterns of development, Route 11 is a gold mine. One can tell, for example, that its more crowded and thriving stretches are those which function not really as highways but as car-oriented alternate downtowns running through the larger cities—Harrisonburg, Staunton, Lexington, and Roanoke. But unlike major metropolitan areas where these distinct sprawl corridors around each town have collided and produced 30 or 40 miles of uninterrupted commercial development—such as U.S. 50 en route to D.C. and U.S. 22 running into Newark, New Jersey—the sprawl along Route 11 is short and sweet.

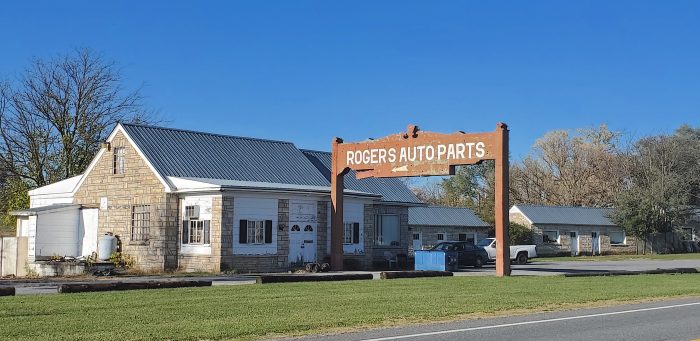

It is also old, and in many cases abandoned. In between the short sprawl corridors, classic main streets, and long stretches of countryside are dozens of small plots housing largely defunct early roadside businesses: general stores, filling stations, diners and small restaurants, motels, auto garages. Many are obviously long-abandoned, probably for longer than they were in business. Others are now used for storage, function as parking lots for work or junk vehicles, or in some cases are residential properties; many a tiny motel lacks a sign and sports a row of mailboxes. What we are seeing here is roadside development circa 1960 or 1970 (which, in a relatively lightly developed stretch like this, still included plenty of structures going back to the 1920s and 1930s), first or second generation roadside development, frozen in time. Embryonic sprawl.

This all supplies a key insight about the origins of sprawl: in the early 20th century, zoning had very little to do with development outside of the cities. Many early motels and filling stations either began as homes with the businesses added later, or were built with a home on-site. The most fundamental aspect of zoning is separation of uses. This very early proto-sprawl does not observe separation of uses. Uses are not only mixed on any given lot, but appear quite flexible over time. For example, a home and restaurant building adds a motel, the motel closes, the home becomes an office for a junkyard. It might even be correct to say that this predates what we now call sprawl. It is more of a relic of the early “auto touring” days.

As the landmark book Main Street to Miracle Mile demonstrates, pre-war roadside development (along with streetcar corridors) is a key evolutionary missing link between the classic main street and the modern suburban-sprawl commercial corridor. A good deal of urbanist discourse on sprawl treats it as a function of government regulation, chiefly zoning. It is true that today’s zoning codes, minus those which New Urbanists have been able to tweak, mostly mandate development in a sprawl style, due to parking minimums, minimum lot sizes, and setbacks, in addition to the overarching separation of uses.

But the patterns that would eventually mature into sprawl mostly arose organically, simply as development scaled to the automobile. Most of the regulatory regime that produced or mandated suburban sprawl came after the fundamental pattern was already observable across America. Nonetheless, this early, organic sprawl as noted still mixed uses, much as traditional town development did. Had it not been for rigid land-use rules, we might well have seen a mixed-use sprawl decades ago, whereas we are only beginning to see something like that now.

As a more general matter, it is interesting to consider that sprawl actually represents a densification and intensification of roadside land use, a filling in of the gaps. It is low density compared to cities and downtowns, but it is high density compared to its embryonic ancestor. At what point, anyway, do “structures along the highway” turn into “sprawl”? Perhaps there is no single answer. But if every urbanist and planner should get out and experience the city as a pedestrian, they should also get in the car and observe the great open-air museum of the bypassed U.S. Highway.

And what of the buildings themselves? They are not beautiful. They are preserved, mostly, in the sense that they have never been renovated or facelifted, not in the sense that they are attractive or even structurally sound. Many are overgrown or partially collapsed. Many are styled in such a way that they’re obviously from the 1950s or earlier. There are very small motels, with as few as eight rooms, or even detached “tourist cabins.” There are boxy rectangular service garages with two bays and large windows, either once-gleaming enameled Texacos, or clones (one service station I passed even had an art-deco glass-block cupola, but its parking lot was so crammed with trucks I could not get a decent photo.) There are restaurants built to look exactly like a Howard Johnson’s. There are lots of single-pump service stations with an overhang extending from a house-like structure.

It is fascinating that many of these one-off buildings reference something that no longer exists. The lack of economic dynamism along here has acted as a preservative, and so the buildings fall apart but remain otherwise in their original state, outliving their vanished chain competitors whose structures have long since been demolished or remodeled beyond recognition. Is physical preservation simply the side-effect of economic disinvestment?

While mature sprawl would entail a densification of this pattern, neglect has thinned it out. It is really just the tunnel vision of the affluent urbanite that gives the impression that America’s land is being gobbled up and paved over. It is striking to consider that the roadside landscape here, in 1950, had more buildings than it does today.

♦♦♦

The Shenandoah Valley’s smaller towns, for which Route 11 is main street, largely have their origins in the 18th century, but most evince the power of the railroads in shaping the built environment. While the larger ones like Staunton and Roanoke are full-fledged small cities, these smaller towns, like New Market, Mount Jackson, Woodstock, and Buchanan, are essentially long assemblages of tightly packed buildings along the highway. There aren’t many back streets or cross streets. You might call this “rail sprawl,” and it is a different pattern from, say, the New England village with its central square. Built environments cannot simply be divided into “sprawl” and “not sprawl.” But despite their corridor-like design, they also sport a great variety of building styles, heights, and uses. Many of these little main streets have buildings taller and more quintessentially “urban” than most of what is allowed by right in suburbia today.

These towns, with whatever their economic engine was long vanished, are not obviously in desperate straits, but they are not young, lively, or hip. They evince a feeling of faded grandeur. Yet despite their small size, they sport beautiful churches, courthouses, and various civic markers and monuments.

The prevalence of this civic infrastructure testifies to two things: that these towns were once much grander and more affluent than they are today, and that even very small settlements once had a strong pride of place.

A common critique of sprawl, that it “all looks the same” and therefore “destroys a sense of place,” is not exactly accurate. Route 11’s small towns more or less “look the same.” But they do not lack a sense of place. Neither, for that matter, do the lonely stretches of proto-sprawl or countryside. There is no objective explanation for why this is, but it a sentiment felt widely enough that there is almost certainly something objective to it.

The Shenandoah Valley itself, despite its long-term economic stagnation, is a place of beauty and potential. There are signs that boutiquey tourism is “discovering” this old urban fabric. One filling station is now, of all things, an AirBnB rental. Route 11 is home to a somewhat famous annual 40-mile, multi-town garage sale crawl. Old theaters remain open, and one has been transformed into a craft brewery. None of this will bring back the fundamental economic function of small towns, which has largely been eliminated from the complex, global economy. But it may be enough to prevent these places from slipping into deep poverty.

It’s easy to see this “old fashioned” landscape and think that perhaps the people here are simply culturally old fashioned, living the Mayberry dream. It is easy to view the built environment as an indicator of values or cultural preferences. But that is mostly not the explanation. This is chiefly about stages/phases/levels of development, that is, intensities of land use. The real estate values and populations here do not support the kind of development and competition that causes (in tandem with zoning) sprawl to proliferate.

The fact that economic stagnation and the bypassing of motorist traffic has in effect preserved an otherwise extinct era of building and town-making is cause for some emotional conflict. Surely it is not worth passing actual people and communities by so that nerdy road trippers can spy a former Texaco garage that would otherwise long ago have been redeveloped. But do the people in these places feel that way? Would they prefer more traffic, more sprawl, more change and discontinuity in their built environment, if it meant more dollars flowing into their communities?

♦♦♦

If the economic purpose of the old towns no longer really exists, the purpose of Route 11’s frozen early sprawl is also obsolete. Along with all the other reasons for its abandonment and stagnation, there’s also progress in automobile engineering. Cars are faster, more reliable, and more fuel efficient. Tires are more reliable as well. Car interiors are more comfortable. Highways simply don’t need a 10-room motel or a one-pump filling station every couple of miles. This frozen-in-time pattern is an artifact of the years in which it arose, and perhaps it should not be mourned or overly studied.

Route 11’s highway graveyard needs no formal preservation. Many of these structures were essentially disposable, and would have been subject to remodeling or demolition had they survived under their original owners long enough. The Texaco architects, or Howard Johnson, would be shocked not that some of their buildings would end up abandoned, but that any of them would still be standing 70 years out.

Yet a certain fascination is still in order. And also in order is a blunting of that fascination as one realizes that a great deal of America—bypassed, neglected, economically and civically in trouble—looks like this. My home of Northern Virginia is less representative of America’s physical and economic landscape than Route 11. The urban planning problems of the Shenandoah Valley are more typical of America’s problems than those focused on in most urbanist discourse.

There may not be many answers, I thought as I took notes in my motel room. But there’s a lot of beauty out here. And plenty of food for thought, plenty of pictures to take, plenty of folks to talk to, and plenty of miles to drive.

This New Urbanism series is supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation. Follow New Urbs on Twitter for a feed dedicated to TAC’s coverage of cities, urbanism, and place.