Not much is left in Whiteflat, Motley County, Texas besides the former school. The county was once booming and would have accounted for rural America’s growth in the early 20th century, ballooning from 139 people to 6,812 between 1890 and 1930. Today there are only 1,200 people in the entire county. Copyright Vincent D Johnson/LostAmericana.com.

There are few scenarios going forward where rural America doesn’t shrink. This is quite evident for people who spend any amount of time outside of America’s more urban areas. That isn’t, however, to say that there isn’t any growth in rural areas.

As we approach the release of information from the 2020 U.S. Census, it is particularly set up to show a shrinking rural America. Some might feel no matter how the numbers come out, that the Census bureaucrats are out of touch with Middle America. But they will probably not be wrong. Rural America really is shrinking.

In hindsight, many small towns and rural communities were almost built with a destiny to shrink. Those in the know have seen this coming for some time. The incredible part, in fact, is that it’s taken this long for it to start happening on a nationwide scale. That in itself is a testament to the life, vibrancy, and love people have for these places.

The fact that so many people have hung in, toughed it out, and stayed behind while others left makes these places a part of our society to be treasured—while at the same time making it almost impossible to save them by the means we’d want to measure them by.

Growth, rightly or wrongly, seems to be the most important measure in today’s world. “If you’re not growing, you’re dying,” the phrase goes; but many of these places are either not interested in growth, or realize growth would change the very fabric of what makes them what they are.

In the beginning of America’s Westward Expansion, towns were set up at distances determined by logistical needs to get their local resources to the rest of the country or the world. The growing number of defunct towns, or even ghost towns, started as early as the 1800s. As trains replaced horses and highways replaced tracks, their routes and the places they bypassed determined the winners and losers in many rural areas.

Just about every state is splattered with place names that are all that remains of a pioneering settlement; Tuxedo, Texas; Cardiff, Illinois; Ardell, Kansas. The number of these will surely increase by mid-century.

Since 1790 the United States has been conducting a decennial countrywide census of its population. In 230 years, not once has the population of rural America shown a population loss—not even with the Great Depression. Many of the “rural” areas of today were at one time the hot, new, exciting places to be. The Wild West, the Oregon Trail, and lands open as far as the eye can see still fill the fantasies of today’s pop culture. Those who came before us raced across this open land in search of making their fortune or starting a better life. They risked their lives and often the lives of their families to build up these places. Yet today the opportunities in some of those places are as long gone, as are many of the natural resources that attracted people there in the first place.

And so, starting this year as the data from the 2020 Census is released, the United States might see its first official rural population decrease. This is not a decrease in growth rate, which has been slowing for a while now. This is an absolute decline in the total number of people living in rural America.

While most Americans know about the main census that happens every 10 years, the U.S. Census Bureau does estimates of regional or larger cities at intervals of 1, 3, and 5 years. In 2015, for the first time in U.S. history, one of those estimates showed that rural America hadn’t just stopped growing, but that it had lost people.

The factors are almost too numerous to list: larger farms needing less labor; regional manufacturing leaving small towns; transportation methods changing, along with infrastructure that made personal mobility and choice easier. Add onto that an aging population and difficulty attracting or keeping young people. The writing has been on the wall for decades.

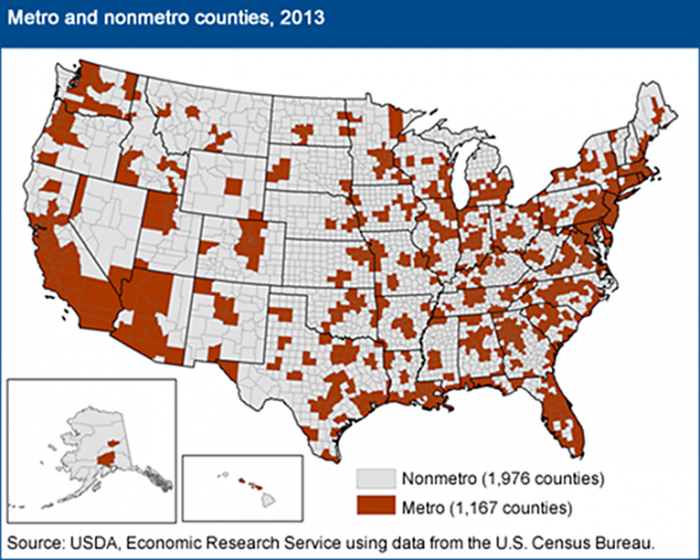

The Census, like all collections of data, is no perfect measurement. One of the ways it has affected how we look at rural areas is with something the USDA calls the Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC). An RUCC is assigned to every county in America and essentially designates it statistically as an urban or rural county.

While the RUCC isn’t overly complicated, an easy way to explain it without a bunch of charts is that there are nine different classifications: classes 1-3 are “metro” or urban areas, and classes 4-9 are designated as “nonmetro” or rural areas. Classes are designated by the largest-sized town in the county and then by its counties’ largest-sized town. Class 9 is the most rural while class 1 is the most urban.

So it goes without saying that counties home to America’s largest cities fall into this first class. However, since these classifications include counties adjacent to urban counties, you occasionally have places like Calhoun County, Illinois—with a population of roughly 5,000—designated as a class 1 metro county, solely because it is adjacent to the St. Louis metro area. While the big city may be a short trip as the unladen swallow flies, this 280-square-mile county is a peninsula formed by the Mississippi & Illinois Rivers that is 50 miles long, and with exception to its northern border, is all but cut off from the surrounding area save for a ferry barge and a single bridge.

At the other end of the classification is RUCC 9, a county that doesn’t have any towns over 2,500 people and is not adjacent to a metro area. Calhoun County, Illinois definitely sounds like it fits that description, as its biggest town, Hardin, has only 1,000 people. However many of the counties that fall into this class are in some of the most far-flung parts of the country, a good distance from the economic possibilities of urban areas, and are without a doubt rural. Places like Loving County, Texas; Arthur County, Nebraska; or Bristol Bay Borough, Alaska.

The point of all this is that, while there’s much talk about the urban/rural divide, there may need to be a little more attention paid to what the urban/rural divide actually is.

At heart, the larger question is, what is “rural”? Does it just refer to the sum of a place’s population? How should census data define what makes a place rural? Has the meaning of “rural” become associated more with a lifestyle than a geographic/demographic region?

Consider Grundy County, Illinois. A little more than an hour’s drive from Chicago, it is just west of where I grew up in a very urban setting. Having lived there from the mid-1970s through the early ’90s, we would visit friends and family in Grundy County’s towns like Morris, Minooka, and Coal City. We’d drive down gravel roads, past farms and fields, over one-lane metal truss bridges, and stop in town on main streets that were filled with stores.

To this day I still describe where I grew up as being the divide between the rural and urban parts of northern Illinois. That area was the country. It was rural, but today that line feels like it’s blurred.

When the USDA first introduced rural and urban coding in 1974, Grundy County had a RUCC of 6. Today it is considered a metro area with a RUCC of 1, matching that of Chicago’s Cook County and many of the surrounding counties that account for the 9.5 million people there.

I still know plenty of people in Grundy, and most wouldn’t consider the area anything but rural. However, they would quickly admit that things have changed, as an influx of new residents has doubled the population since my childhood. The economic opportunity that comes with being so close to a metro area is evident with a drive along the Interstate, as shipping warehouse after shipping warehouse has filled in former farmland, alongside new subdivisions. All of this offers jobs and economic opportunities that weren’t present in this rural county 40 years ago.

With just under 2,000 of the country’s 3,143 counties designated as nonmetro/rural after the 2010 U.S. Census, a very real possibility exists that the overall rural population of 46 million may indeed decrease. Whether this is due to the actual shrinking of rural counties, or more of a statistical artifact due to rural counties growing and becoming designated as urban, remains to be seen.

When I visit Grundy County today, I wonder whether rural America as a whole is being penalized for its success. If growth is the definition of a strong rural area, how long before that area is no longer considered rural? The USDA does have a lot more to say about this than the simple explanation of the classification system here, but the question is very much live and open.

Looking across the country, one sees explosive growth in cities like Austin, Texas; Charlotte, North Carolina; and Columbus, Ohio. Surrounding them are places that are currently small towns and counties seeing the same changes Grundy County did. The people who lived there before this new growth may still feel rural, but most likely their area’s success via proximity will place them and the rest of the population in the urban count, while the remote counties will continue to shrink and bring down the total rural population count.

If only there was a term to describe these places and their saga. Maybe we could call them “postrural.”

Vincent David Johnson is a Chicago based photojournalist, filmmaker, and the person behind the Lost Americana documentary project. When he’s not working on Michigan Ave., chances are you can find him in rural America checking out a town you’re not going to see on a travel show.

This New Urbanism series is supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation. Follow New Urbs on Twitter for a feed dedicated to TAC’s coverage of cities, urbanism, and place.