My dad moved to Cincinnati from a small farm-and-factory town in central Ohio. His parents both worked for the post office. For entertainment they would listen to the Reds on the radio, or take folding chairs and go watch the one train that came every day and see what interesting cars were hooked up and who got on and off. When he moved to the big city he was surprised and delighted to see that a man he didn’t know any better than to call Bob “Dye-lan” was playing at the Taft Theater.

He became a radical in college. He made friends with a few people who would go on to become charter members of a society of Ohio-raised and locally educated left-wing families, which formed the social universe of many white kids growing up in the inner-city around the time that I did. We went to school in integrated public magnet schools, and we lived on majority-black blocks, but the white children in this interconnected set were our first close friends and first crushes and quite often the people we ended up marrying. The parents were union organizers, social workers, mental health nurses, or assistant city planners, who had resisted the wave of white flight. The kids went to liberal protestant churches—ours was Quaker, most were Unitarian, and for Cincinnati there was a disproportionate number of Jewish kids—and were expected to go on to liberal arts schools in the Midwest or the Northeast. This was the final tall step in an intergenerational march toward enlightened and liberated modernity, which for my family had begun when my great-grandparents left cowboying in West Texas to come north to find work in a cast-iron pan factory.

It was a community that from afar might seem easy to tar with the values of a strand of American liberalism that was developing at that time—one that had a fatal inability to differentiate between the concepts of change and progress. But this would be to misunderstand how politics work in Ohio. It was true that these people, like white liberals of their broader generation, had grown up with a set of notions that seemed dogmatic and at times extravagantly performative. They could treat almost any symbol or value of the generation they’d grown up rebelling against as a sign of backwardness and oppression. If I was ever going to have become a reactionary—and it may reduce the interest-value of this piece somewhat when I say that I haven’t, and there is no twist coming later where I reveal that the hypocrisies of liberals have finally driven me into the arms of the right—I would trace it to the moment I asked my mom if we could get an American flag to put on the lawn. She said, plainly, and accurately, that it wasn’t “the kind of thing we really do.”

But if these people came into adulthood during the culture wars of the ’70s, they came into maturity under Reagan. They began raising kids under the uneasy duopoly of power shared by Bill Clinton, signer of NAFTA, and Newt Gingrich, a passionate futurist and breaker of traditions. Left-wing politics in Ohio—from the unions that were lonely voices against NAFTA to the interracial community organizations that were some of the few voices that spoke up against urban renewal, gentrification, and welfare reform—often took the form of a rearguard defense against disruptions to ways of life that had managed to constitute themselves in the factory towns and inner-cities.

This is something people often tend to miss in the endless thinkpieces dissecting how a state that twice handed Barack Obama the presidency became by 2020 a state that voted more strongly for Trump than Texas did. How this happened is supposed to be a great political mystery—the great American political mystery in some ways. If we could agree on why Ohio fell so strongly for Trump, it seems reasonable to think that we could agree on what was wrong with the politics that came before. From there maybe we could agree on how to move forward. But this would take admitting that our politics are shaped by deeper forces than what we used to allow into them.

Ohio’s modern political culture was shaped by migrants, black and white, from rural America and the fringes of Europe, who for a very brief window of time managed to build a sense of stable prosperity and communal feeling. This bred a society shaped by an aching memory of the places that had been left behind, and a deep attachment to the stability and sense of order that they’d sacrificed the older life to gain.

It was only in the ’90s that we really solidified our national two-party consensus that it was backward, silly, and entitled to expect this kind of life. It was the local left, a people who blended a belief in universal values and a grounding in very regional customs and history, that carried on a lonely resistance. They were told they were standing in the way of progress. They were told that they didn’t understand where history was headed.

My dad left college and moved to Adams County, Ohio, where he taught school and worked part-time in tobacco fields. He got very good at bluegrass guitar, and to this day, like many of his country-bred friends with whom he formed Trotskyist groups and racial-justice-awakening circles, he is a fantastic and irreplaceable repository of country anecdote and song—the kind of thing you can’t sell a book on, but that creates a sense of being a part of a world that goes back very deep. He helped start a group called the Urban Appalachian Council, which lasted for decades after its founding as a storefront community center, and helped migrants from the coalfields deal with the very material realities of poverty and lead poisoning in the troubled neighborhoods where they congregated and where he lived. But it also helped people struggling with the less material problems of split families and dislocation that he—having left his country home and family to go to college, rather than because he was fleeing strip mining and gun thugs—could not always feel comfortable articulating about himself.

My sisters and I grew up in and out of Adams County and Eastern Kentucky, using outhouses and eating morels fried with squirrel meat, and waiting politely for miners with black lung to find their breath to continue a conversation. We also grew up watching as dad had friends murdered and city development interests mocked people like us who fought to keep what was now a mostly black neighborhood intact, in the face of the people who eventually succeeded in turning it into a glassy destination of boutique-shops. We grew up so surrounded by the songs of lost home that we all often felt confused about why we were being brought up where we were, if it was so much worse than the formless place that we ourselves had not even left behind.

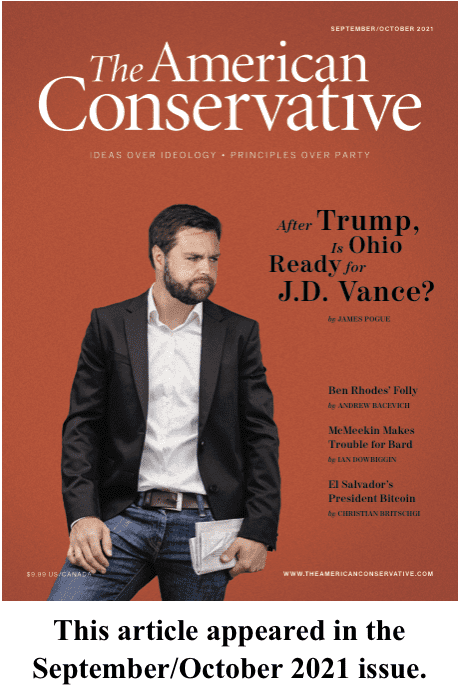

It’s probably obvious by now how this ties into a Senate race that I think could end up being as consequential for the political future of America as any of the presidential elections Ohio ever decided—if in fact J.D. Vance can get out of single-digit polling in a crowded primary field, and advance his program to a country that may be very shocked to hear it. He is only a couple years older than I am, and now possibly Cincinnati’s most famous political figure. I will admit that he’s dogged me somewhat as I go through my own process of chronicling change and upheaval in the modes of life in Southern Ohio. When he moved back to town he moved into the house where I had my first beer and my first high-school kiss. Being on the left, being from Cincinnati, being to a small degree proximate to the meritocratic world that elevated him, having my own family shaped in inexpressible ways by a rural migration—all of that put me in a position where I was often asked to write pieces mocking him or dismissing him as a fraud.

It would have been pretty easy to set myself up as a kind of counter-explainer to the redneck Virgil he became, after Donald Trump won Ohio and set off such a storm of confusion about how the politics of America’s great bellwether could have been reshaped so quickly. I think I didn’t do this because no one in liberal America then would have taken me seriously if I tried to explain why I thought Trump hadn’t reshaped anything, and had almost by chance managed to access a deep desire for stability and a sense of belonging that I thought formed the basic political character of the state. I thought Vance understood this force better than almost anyone in America. But I hadn’t ever really expected him to turn Ohio into an experiment in how this feeling can be translated into a national political mobilization. And I hadn’t expected to be so worried by what that looked like.

* * *

I hadn’t been back to Cincinnati for a couple years until I came back in July. My uncle had cancer. He was our family’s last living representative of a brass-buttoned and proper merchant-class world on the city’s East Side, a place that my mom had worked hard to get herself away from even before she married my father. It was a rude coincidence for me that I’d been wanting to write about Ohio politics right as this uncle seemed to be about to die, partly just because the house Vance had moved into was one of the great lodgements of this East Side culture. I had spent time in that house because the girl I knew who grew up there—my junior-year prom date—had been the richest person I knew, and had the biggest house of anyone we knew, so it was our natural party spot.

The people who lived in those houses formed the local mini-aristocracy, a culture with enough money and influence to reproduce itself through the polo-shirted generations, as through the decades worlds collapsed all around it. Rob Portman lived down the street from my grandmother for a while, before he jumped from Congress to be George W. Bush’s trade rep and then a senator. Across the street lived the Sittenfelds, where the daughter Curtis had become a famous author, and the son P.G. would soon make a triumphant return from a Rhodes Scholarship to run for city council. Then he made a stab at running for Senate against Portman. Now Portman was retiring from the Senate, and P.G. was facing federal charges in a bribery scandal. And Vance—who had made his name as a representative of the country-migrant white culture long regarded with horror by the prim Republican elite made up of the descendants of people who’d migrated from Virginia many generations earlier—had come back with a degree from Yale, and millions of dollars from publishing, film, tech, and high finance, to buy this big white house and run for the seat Portman was vacating. But he was still a scourge of elites. It was all a little thick to try to process.

I knew his chief opponent, too. I met Josh Mandel when he was still a pencil-necked young state treasurer, and I was a 24-year-old covering the Obama–Romney election in Ohio in 2012. It was a surreal time. The Romney events in that election all seemed incredibly grim—Lee Greenwood playing under drizzle to crowds of men with aching joints, who watched as a parade of statewide mediocrities would come to give warm-up imitations of Paul Ryan. No one cared about their fiscal policy ideas. When people talked about Lost Liberty at those events they had a habit of starting at Obamacare and ending up at how nobody went to church anymore and how the Elks hall had been replaced by a Dave and Buster’s. They talked about how Clinton had killed the unions. They talked about lost family farms.

Or they talked about race. I’ve been to plenty of Trump rallies, but I never saw anything like the racist paraphernalia on sale and display around the Romney events in Ohio. In Mansfield I once walked alongside a black newspaperman as we passed a bearded old man in aviators and a U.S. Navy cap selling stickers and buttons. He unsubtly readjusted a display copy of a sticker reading “Don’t Re-Nig in 2012” as we passed his table. This was all of a piece, if you could see what was happening.

Mandel is a vile but canny figure. The Cleveland Plain-Dealer wrote that year that he was “known for his reluctance to voice clear and specific thoughts on current issues.” He gamely played along as a surrogate for Romney, the political apotheosis of our elite national consensus that treated GDP figures and the power of markets as the only true values left in America. I was there the night before the election, when Romney held a last rally in a cold and grim aircraft hangar outside of Columbus, and failed to manage a planned dramatic entrance because the pilot couldn’t navigate the campaign jet into the hangar. Mandel, who was running against Sherrod Brown for Senate and working with the language of politics that constrained him then, could barely manage an applause line.

Now, liberated, he’s become a wan but effective imitation of Trump. He talks a lot about Judeo-Christian values, but his politics seem to be mostly based on the idea that tweeting about how liberals hate bass fishing and the family is an act of extreme reactionary bravery in America now. It’s pure tit-for-tat culture war, and it’s comical to imagine Mandel trying to articulate how he came to his sense of ownership over the deep values of the Ohio electorate. More to the point, it’s impossible to imagine that he could articulate a politics that could address the structural, global, forces that really disrupt modes of life, and which are held up by much more powerful interests than the woke armies of Twitter.

I don’t personally think that there was ever a way out of this trap. The ideological forces at work were too powerful, and had been working for too long, to think that anything Obama could have done would have changed where we were headed. But it’s still strange now to remember that in 2008 he won almost all of Ohio’s industrial northeastern counties, and even won counties in the Appalachian southeast of the state. It was easy for pundits from faraway to parrot the line that he won those places because he represented a break from the past, that the turkey-gun set was finally beginning to sign on to the global technocratic order. But it was the exact opposite: he won the industrial Midwest in 2008 because he promised to support pro-union laws, and because he was the closest thing that anyone had seen in a generation to an anti-globalization candidate. Obama made a very effective insinuation that he was a candidate that would help arrest a sense of creeping chaos that was overtaking the lives of people in places like that. I still remember the radio ads he ran in Appalachia featuring an endorsement by Ralph Stanley. “I think it’s about time we had a leader who was on our side,” the inventor of bluegrass said. “Children shouldn’t have to leave our communities to find work.”

It was never actually complicated. Before Trump, there hadn’t been a way to give electoral expression to the feeling that the constant change that had swept over America in the last 50 years had not necessarily represented progress. Then there was. It’s confusing to me why we had to argue about this, because this explanation contains all the other major explanations that people tend to offer for Trump’s pull in the state—it was racism, it was a revolt against globalization, it was an expression of economic desperation. It’s not that this feeling was the only force deciding how people voted in Ohio. And it’s not that the people who felt it all ended up voting for Trump. But enough people felt it, and enough people saw voting for him as an expression of the feeling that it reshaped state politics instantly. It happened so fast that it was easier to look for one issue, for one neat trigger, but to even think this you’d have to misunderstand how different the various regions of rural Ohio are from each other.

* * *

I had trouble explaining to my parents why I wanted to write this piece. My dad loathes J.D. Vance as much as his Quaker-convert heart can loathe anyone. He thinks Vance has created a caricature of Appalachian identity, in service of a right-wing politics that’s as viciously exploitative and disruptive of the lives of poor people as anything that came before it. My mom, a drug counselor by trade, once actually put Vance on a panel she’d put on about the opioid crisis in Ohio. But she had a slightly different worry: that I was making myself a useful idiot, for someone who was at best an attention-grabbing also-ran, and at worst someone who might be our next Mussolini.

I worried about this too. I actually had to ask an editor at a conservative magazine (not this one) what people on the right thought of him, because I suspected, correctly, that his candidacy was the subject of currents and conversations that I didn’t have ready access to. He said he knew a few Vance acolytes in D.C.

“I think their hearts are in the right place,” he said. “But they are also very young and online and products of the elite culture they’re rebelling against. So there’s this weird parachute-candidate feel to the whole thing. It’s like bourgeois communists walking onto the factory floor and telling the workers, ‘Let us represent you!’”

“Vance is like a native elite in a colonial setting,” he said. “Somewhat alienated from the dominant imperial culture, and wants to defend his people against it. But has passed through its institutions, alienating him from the people he wants to represent.”

I suppose that on some level I considered myself one of these people he wanted to represent. That was why I was interested. He was also the only politician I’d ever really encountered who had a theory of upheaval that encompassed both the cultural and economic spheres. But I hadn’t really put together how much of a considered political project he had going, or how much this project was conceived against a set of elites that I wasn’t sure whether or not I belonged to.

We met at a diner called Sugar n’ Spice, where my dad used to take me after Karate class. I texted my best friend from Cincinnati, a black guy who had grown up in the vicinity, and he wrote back immediately. “I guess pancakes go perfect with white nationalism.”

I was surprised by how elite he actually appeared, thinner than the pictures I was used to seeing on Twitter, and wearing the trimmed beard and slim suit that I have come to think of as a uniform of thirtysomething guys I know who work at ad agencies or movie studios. I asked him, realizing that honestly I didn’t know much about what I was asking about, to explain his vision of right-wing populism.

We started by talking about industrial policy, and we chatted over the mundanities of whether it would be possible to work out a system of protectionism and tariffs that would make America make stuff again. “That’s the experiment I’m running in real time,” he said. I wrote that quote down because it seemed like a very grand way of putting things, for a candidate who’d never run for office, and was polling at 6 percent in an eleven-way primary.

But I hadn’t realized how grand his project really was, or how it was not so much just a product of one man’s ambition and ideas, but a very thought-out product of a worldview organized by people who operated at a much higher echelon of American society than I apparently had a very good picture of. He talked about how he and Peter Thiel were recalcitrantly attached to America, something that couldn’t be said for “other elites,” as he phrased it at one point. He had a structural conception of, and casual intimacy with, this class that I’d never heard a politician even try to describe before. Everything we talked about seemed to come back to this. “The sense of pride in where you come from,” he said when we got talking about cultural politics, “I think our ruling class is actively trying to destroy it.”

This hit on the thing I’d wanted to meet him to ask, and that had been bugging me ever since I was old enough to think through my politics. I’ve only voted once in my life, for Obama in 2012. It was because I viewed Mitt Romney as a unique, almost world-historical threat to the last things that gave live meaning and value on this planet. I saw him as a living incarnation of a world where soon nothing would have any value or meaning outside of its value in the market. I viewed my sense of belonging to America, and the store of value I held in the historical forces that had shaped me, as something that I shared with other Americans and with anyone who had a sense of cultural or national belonging, as a kind of resistance to this direction I thought the world was headed in. This is why I’d been so depressed after 2016, when even the faintest affection for the flag suddenly became an unsubtle marker of what side you were on in our grand national culture war.

So I asked him if there was some version of his project that didn’t have to be exclusionary. I was surprised when he used the word right back at me. “I think that any national project has to be on some level exclusionary,” he said. He talked about it as a foregone conclusion that the only way left to have a sense of cultural grounding in America was to wear it as an oppositional identity, against an elite that I still wasn’t sure the makeup of. “The thing that I worry about, and that a lot of people I’m working with worry about, is that if we fail, it will be because the American regime itself is too turned against the communities that I came from.”

I asked him to describe the contours of this regime. He thought for a minute. “My basic intuition is that about 20 percent of American children recognize that what they will be judged on is whether they get into an elite college,” he said. “And about 80 percent of American children have no idea. And I think if that’s the thing you have in your mind, if you’re in that family and you’re in that orbit, then to me that’s the biggest thing.”

“I think American politics is either going to be a place of permanent, effectively institutionalized civil war that ends in genuinely bad things,” he said, “or the American right is able to assemble a coalition of populists and traditionalists into something that can genuinely overthrow the modern ruling class. There is no way to get to where I want to go with 52 percent of the vote. It has to be much bigger than that.”

I’ve long since given up looking for a political home in America, and so I didn’t feel the pull I might once have hearing him talk. There was a time when I would have found the combination of an economic policy geared towards the working class combined with a cultural grounding in the place where I was from to be very thrilling, illicit, intoxicating to imagine. But one lesson we have learned from a cultural order where the values of college-educated liberals hold sway, is that things can turn dark when you get into power, and that it’s easy not to notice what you do with power once you have it.

The liberals of my parents’ generation didn’t even notice when their values became ascendant, because in the now-permanent revolution that our culture has become, it was very easy to pretend that they were still fighting against the repressive hegemony of family-values conservatives. They didn’t notice how their cultural values ended up being plenty concordant with the values and interests of our true oligarchs. They didn’t notice how values that were supposed to be about liberation left half of America feeling constrained to change, and they didn’t understand why this had anything to do with them. “I think our people hate the right people,” Vance said to me as we wrapped up. It’s an easy thing to think now when the stakes are lower than they soon may be.

James Pogue is the author of Chosen Country: A Rebellion in the West.