Wife of a pea farmer at a vinery near Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, June 1937. (Photo by Russell Lee, U.S. Resettlement Administration via Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images)

Historically, a weakness of the Republican Party has been the economic divide between the party’s donor base and its voter base. The grassroots and the establishment have divergent interests.

The party’s donors have been corporatist and favorable to free trade. A large concentration of these donors are in the banking and finance sector. In general, this class has benefited from the party’s economic policies.

On the other hand, the party’s voters are members of the middle class or from families that were once middle class. These voters believe in the working class America that I grew up in. They recognize that the Democratic Party, which used to claim (and, falsely, still tries to claim) that it is “for the little guy,” has instead become the party of the corporatist elite, globalism, and of big government—in short, the party of State Corporatism.

Recently, many of these voters have become so-called economic populists. Their views vary widely, crossing the spectrum from right to left, but what they have in common is an understanding that the system is not working for them, and hasn’t been for a long time.

It is fashionable to argue that the economic populists are dangerous people who storm barricades and seek to overturn valid elections. With very few exceptions, they are not. Economic populists are those still in the fading middle class, watching their prospects erode, and those whose families used to be in the middle class, but no longer are.

Economic populism has a long political history in the United States, dating to Henry George’s electoral bid for mayor of New York City in 1886. Its roots lie in the wheat fields of Kansas, the steel mills of the industrial Midwest, and the former ghettos of New York City.

In the 1880s and 1890s, these geographies produced a class of people who found themselves unintentionally and irreversibly connected to an economic system that, for their purposes, had three main characteristics.

First, it was not local. The economic system to which they were subject was strongly affected by market forces that were centered in faraway places like New York and London and controlled by people they did not know.

Second, the system was not working for them. The benefits that accrued to them from the prevailing economic system were both low and volatile. For workers, this meant low and volatile wages. For farmers, this meant low and volatile grain prices.

Finally, money was a cause of economic uncertainty. The international gold standard required inflows and outflows of gold as international trade surpluses and deficits fluctuated. This, in turn, meant that the quantity of each country’s base currency fluctuated, causing fluctuations in price. Farmers, who represented most of America’s property owners, argued that this fluctuation hit them the hardest, especially during downturns. In a depression, America’s net exports fell. This required gold outflows, which decreased the quantity of money, thereby decreasing price levels. Much of this price drop was felt in commodities such as wheat and cotton. In short, when depression hit, farmers sold lower quantities of their produce, at lower prices.

This led to farms being lost to banks, and those who had capital could accumulate more and more land at the expense of the smallholder. Farmers demanded price stability by demanding that silver be used as a partial monetary base—the “Silver Wing” of the Democratic Party.

On the other hand, for industrialists (the corporatists of their time), economies of scale paid off in the form of monopoly power and monopoly profits. Men such as J.P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, John Rockefeller, and Cornelius Vanderbilt built fortunes by conducting economic activity at massive scale.

The conditions of the 1890s are essentially identical to our own, though in different guise. Today, scale rules the economy. Globalism means that economic power and decision making is not local. Volatility, both in stock market returns and in job prospects, characterizes the economic life of most people. Male median wages have not increased in real terms in over 30 years. And, finally, we are in a new gilded age in which technology titans and hedge fund owners are billionaires many times over while over half a million Americans are homeless.

The conditions of the 1880s and 1890s led to Henry George’s near victory in the New York City mayoral race. They also led to William Jennings Bryan’s presidential candidacy, which transformed the Democratic Party into the party of the worker and the Republican Party into the party of business.

Heading into the election of 1896, the Democratic Party was sharply divided between those who supported business interests and those who represented economic populism. The business interests were the party’s donor class, while the Silver Democrats were its voter base.

In the election of 1896, the Silver Wing—that is, the economic populists—prevailed and transformed the Democrats into the party of the working class. For the next 100 years, the Democratic Party would be the party of the middle class and, because America’s democracy has always depended fundamentally on the middle class, the party of “America” writ large. From the mid-1930s to the mid-1990s, the Democrats controlled the House of Representatives in all but two election cycles and the Senate in all but five.

Today, the Republican party’s great divide is identical to that of the 1890s Democrats. And because the economic facts on the ground are the same, the political facts on the ground are similar as well. As demonstrated by the economic research of David Autor and his colleagues, Donald Trump’s election in 2016 is due in very large part to the rising tide of economic populism. It is fueled by the uncertainty and decline faced by the American middle class, the former voting base of the Democratic Party.

In the same way that the Republican Party of the 1890s chose the path of corporatism, the Democratic Party of 2022 has also made that choice. It obviously stands with a woke corporatism and a form of social engineering that, from the perspective of most of America, is a heavy-handed managed decline of the middle class. The Democratic Party of 2022 has unfortunately become the party of the elites.

The Republican Party, on the other hand, has a choice. The stakes facing it in this election cycle are the same as those faced by the Democrats in 1896. The Republican Party has an opportunity to represent the worker and the forgotten men and women of America. It has an opportunity to remember those who have lost hope in the American Dream. It has an opportunity to refranchise normal Americans.

Below, I describe and make the case for five economic policies that would refranchise the forgotten middle class. They are designed to foster widely distributed ownership of productive assets. They return us to what used to make America unique and what made it impervious to Marxism and its close cousin, socialism, namely that the means of production—assets—were widely owned by regular Americans. They are examples of what I call “Wide Asset Ownership” (“WAO”) policies.

Let’s Start with a New American Homestead Act

Perhaps the most important way that Americans have historically acquired assets is through homeownership. One can argue that the American Dream is almost synonymous with it.

A crucial reason for this is geographic. America is a big place. Space is abundant. Therefore, housing has always been cheap relative to its cost in other countries.

Over about the last two decades, against our history and despite our abundant geography, housing has become scarce and expensive in large portions of America. Perhaps no one has analyzed the causes of high housing costs more carefully than economist Edward Glaeser. One of Glaeser’s main findings is that the degree to which price exceeds what he calls the “minimum profitable production cost” (the minimum price at which housing could be supplied and still be profitable for a builder) is determined largely by zoning and other building regulations.

A recent paper by Glaeser demonstrates the powerful effect of permitting and zoning on housing prices. Using data for the period between 2000 and 2013, Glaeser finds that markets in which permitting has been most restricted are the markets in which prices are very high relative to production cost. By contrast, markets in which permitting is generous are those with affordability.

The way to think about this is as follows. Supply restrictions in the form of permitting and zoning restrictions benefit those who already own a house by increasing housing values. They also allow builders to sell new homes at prices well above minimum profitable costs (i.e., a competitive price). This amounts to pulling the economic ladder up behind them, pricing both the new and existing housing stocks at levels that are increasingly out of reach for young people.

This is a tragedy. America is a huge country with abundant land. By restricting Americans’ right to build, we are eliminating the benefits of this endowment and doing so in a way that differentially harms younger generations.

A second problem is that central banks have injected so much money into the global economy, that money is chasing virtually every kind of asset. Housing is no exception. Even single family housing is now seen by hedge funds, REITs, and investment banks as an “asset class.” These investment firms are now bundling together houses to create new financial instruments that pay out a share of the rental income from large portfolios of homes to investors. Some of them are buying entire neighborhoods to convert them to rentals.

This is a significant problem. At a time when housing is already supply constrained, demand from investor groups with tremendous access to low cost capital forces young families, who do not have easy access to capital, to compete with those who do. It is a classic example of pitting workers against capital. It gives rise to a permanent renter class. It is deeply un-American.

Republicans should propose a New American Homestead Act. This would have three main components.

The first would entail the use of state and local block grants in a manner that would incentivize generous permitting and penalize stingy permitting. This makes sense, as such grants should be allocated to induce and complement two things: lots of new home builds and family formation.

Second, it would make use of the inventory of approximately half a million abandoned homes in the United States. The federal government would create a fund by which it would purchase and resell abandoned homes to any qualified participant. Qualification for this program would favor young people, and the program would be means tested. Along with a likely dilapidated house, qualifying participants would obtain a forgivable loan equal to an amount determined by local banks and appraisers to be necessary to bring the home back to a livable state. This would not only increase the supply of homes but would enhance America’s housing stock and help its suffering communities.

Finally, the New American Homestead Act would sharply curtail the purchase and rental of homes by financial institutions and other corporate interests. This limitation would hinge on one main criterion: access to low cost capital. Large financial and other corporate entities have access to capital markets that individuals do not. This means that they can afford to pay more for a home (that will be converted to a rental) than young people and young families. They are crowding out the young, and this needs to stop.

Personal Data Ownership: Let’s Have a Digital Homestead Act, Too

Data is the new oil. It is perhaps the most valuable commodity in the global economy. And every one of us emits it by simply walking around.

Most people think of data as a privacy issue. I believe it is a property rights issue. There is a reason we say “our data” rather than “Amazon’s data” when we talk about data that pertains to us.

Given this, I believe that Republicans should pursue a Digital Homestead Act to complement the New American Homestead Act described above. This would declare that all newly generated data pertaining to American citizens is owned individually by them (leaving the existing stock of data in the hands of the large technology companies that currently own it).

This would allow regular Americans to lease their data to Big Tech and to advertisers—or not. They could decide to opt out of the prevailing corporate surveillance/advertising system.

While I am confident that private firms would step forward with blockchain technologies and digital platforms to facilitate the storage and leasing of Americans’ data, if necessary the Digital Homestead Act would also allocate federal funds toward developing the technologies needed to do this.

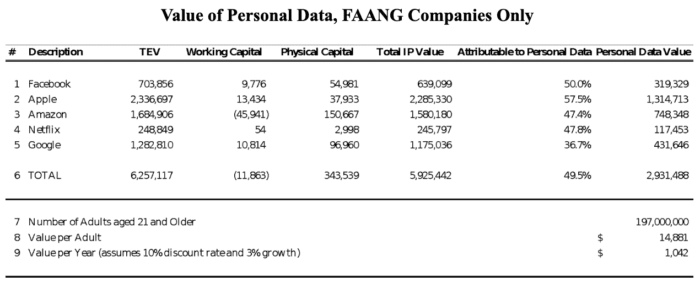

One way to estimate the value of personal data is to examine the enterprise value (the total value of the capital of a company) of technology companies that rely on such data to run their businesses. This enterprise value, less the estimated fair market value of the physical, financial, and non-data intangible capital of these companies, is an upper bound estimate of the value of the vast oceans of data that these companies have gathered and organized about the American people.

Over a year ago, I performed such an analysis and arrived at an estimate of around $2.9 trillion for the FAANGs only (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google). A summary of the analysis is given in the accompanying chart.

As shown, even limiting our value estimate to these five companies, we arrive at around $15,000 per U.S. adult, or profits earned by corporations from this data of around $1,000 of income every year. Given that the FAANGs represent only a small portion of the personal data owners in the world, the annual income that personal data ownership represents is a multiple of that $1,000, perhaps a large one.

Personal data ownership would also have the effect of reallocating a significant amount of political power to individuals. It would create an extremely strong disincentive for technology companies to cancel people. For example, Facebook, Twitter, and Google, whose businesses depend on their ability to target advertisements, can afford to wade into politics because they “own” our data. If instead people could opt out of the system by withholding their data from data markets, these companies would learn quickly that angering people of one stripe or another by canceling important personalities is bad for business.

This in turn would mean that we could use the market, rather than the government, to regulate the problem of cancellation. Indeed, the decentralized nature of the internet would ensure that numerous services would spring up that informed people of cancellations or other political activities by companies that rely on their data.

College Debt: An Educational Homestead Act

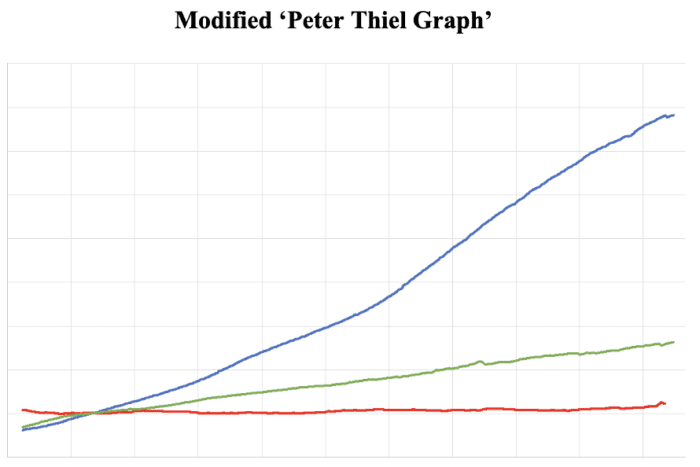

The famous “Peter Thiel Graph” shows rising college tuition costs compared to inflation and median earnings for college graduates.

For those with college debt, the bottom half (ranked by income) now have an average debt-to-income ratio of 1.0. This means that if their income growth rate is less than or equal to the interest rate they pay, then more than 100 percent of their income growth will be eaten up by interest payments. Note that this says nothing about the principal balance (the debt balance) that they also have to repay. Even if they never pay down the principal on their student loans—that is, all they ever pay is interest payments on their student loan balances—if their interest rate exceeds their income growth rate then all of their future income growth will go to pay interest.

The implication is that education has failed to deliver increases in income that exceed its rising cost, and that for a very large percentage of college graduates with college debt (at least half), there is a high chance that their income growth will be eaten up by interest and principal payments. Education is no longer cheap and functional. Increasingly, it produces dependence.

How do we fix this?

The answer lies in the fact that education is intrinsically a very inexpensive thing. As Matt Damon’s character says to the Harvard student in Good Will Hunting, “You could’ve learned all of that for $2 in fines at the library.” Ideas are free (a pure “public good”), and conveying them through teaching is a relatively inexpensive form of production.

The problem is that over the past three decades colleges and universities have bundled all kinds of other services—research staff, sports, fitness services, counseling services, spas, etc.—with the education that they provide. Furthermore, they have attached large bureaucratic administrations to this bundle of services. Well over half, and by some estimates as much as 80 percent, of the cost of a college education is not the cost of a college education. It is the cost of the “college experience” bundle.

My proposal is that colleges should be forced to unbundle and separately price their services. The result would be that students would be allowed to buy just the education services—the classroom time they need to obtain a college degree—if they wish. Practically, this means that they would pay their share of the salaries of teaching professors (I would specifically exclude the salaries of “research professors” who do not teach the next generation; at present, a sizable share of the cost of college education covers the salaries of so-called research professors who do nothing but publish articles in academic journals that almost no one reads and that most people now recognize produce a huge babble of unverifiable “results”), the cost of classroom infrastructure, and some amount of directly allocable overhead. The same unbundling would apply to room and board, transparent pricing that students could either take or leave.

If students only want the classroom time that they need in order to gain access to the American Dream, that’s all they should have to pay for. On the other hand, if they want the full bundle, they can pay for that, too.

Such a policy would dramatically decrease the cost of a college credential, perhaps by as much as 60 to 80 percent. It would reopen college as a pathway to the American Dream for millions of young people.

Stopping Corporate Discrimination Against Small Business

Politicians frequently argue that regulation harms “business.” Why then is most regulation in the United States the product of lobbying efforts on the part of large corporations?

Economists have studied this for decades. The answer is that regulation is a way for existing large firms to raise the cost of entry into their industry. Regulation also favors large firms over those that are small, as new entrants almost by definition are. Regulatory compliance is a fixed cost. Large firms can spread that fixed cost over a large amount of output, so that the per unit price increase that they need to cover the cost is low. Small firms, on the other hand, are forced to spread the fixed cost over a smaller number of units sold.

In short, regulation is a kind of redistribution of business opportunities away from small operators to large existing incumbents that have scale. Regulation is a way for existing large businesses to pull up the economic ladder behind them so that no one else can climb up. And it’s working. In 1980, Americans were creating some 450,000 new companies. In 2013, they formed 400,000 new firms, despite a 40 percent increase in population.

I know from my career as a consulting economist that large portions of the Code of Federal Regulations are actually written or edited by the legal advisors and legal departments of large corporations. Anyone can go to Pro Publica’s lobbying database to find new lobbying registrations, complete with descriptions of the ultimate corporate sponsor and a description of the regulatory benefit that the sponsor seeks to obtain.

Measured by the number of pages found in the Code of Federal Regulations—currently around 200,000—one can see that the burden has increased substantially to the point that it is probably impossible for anyone, even lawyers, to have a reasonable understanding of all of the rules that apply to them.

My proposed remedy is a kind of regulatory amnesty for small business. This proposal involves a simple minimum regulatory regime that would exempt small business from all federal regulations imposed since 2000 and would substitute a basic, clear, and commonsense set of rules for any businesses with revenue under $100 million. Those rules would be limited to the ink that can be spilt in under 1,000 pages rather than the 200,000 pages of Federal Regulation that currently apply.

In implementing the simple minimum small business regulatory regime, I would use a set of regulatory standards developed by economist John Cochrane. Cochrane proposes replacing the complex “cost-benefit analysis” we use today with a set of simplicity, accessibility, and timing (sunset and review) standards.

Bring Back Main Street by Bringing Back Fair Trade Laws

Main Street America was a thriving place because it was full of small retailers. My great-grandfather was an example of this. He was a butcher whose shop was on Benedict Avenue in Norwalk, Ohio. Everyone in town knew him, and he knew them. His experience was no different from that of all of the other retailers on Main Street and Benedict Avenue—including that of my other great-grandfather, who owned a local piano store.

Thriving Main Streets happened in large part because there used to be laws that allowed manufacturers to set the price at which all retailers had to sell their products. Economists called this practice “resale price maintenance.” The more common term was “fair trade laws.”

Fair trade laws operated at the state level. They either required manufacturers to set a uniform price at which retailers had to sell their products or, in their less heavy-handed form, allowed manufacturers to enter into contracts with retailers in which the manufacturer promises to require all retailers to sell its products at the same price.

Small manufacturers bringing new products to the market benefited from this because they could offer new and often more expensive products (small manufacturers lacked scale) of higher quality than existing products. In other words, new manufacturers had an opportunity to compete by creating products of higher quality than those of incumbents.

Small retailers also benefited. What fair trade laws did for them was eliminate the advantage of scale—the massive advantage that we now see Walmart and Amazon deploy against small retailers. Massive economies of scale in retail means enormous pricing power by the largest retailers.

It is very important to understand that these laws did not eliminate competition. Rather, they forced retailers to compete on the basis of service. Retailers who were more attentive to their customers, or who offered better product service (repair services and replacement policies), were the winners in this retail industry structure.

The most fundamental effect of such laws was that they created Main Streets all over America. Small retailers like my two great-grandfathers thrived. Fair trade laws meant that little guys like my great-grandfathers could get into business and compete. They did not have to worry about the possibility that an Amazon or Walmart with massive global supply chain efficiencies would easily drive them out of business. Fair trade laws meant that little guys could own assets. They owned inventory, retail display cases, and delivery trucks. They owned the means of production.

These little guys were not rare. There were hundreds of thousands of them, all over America. They were the backbone of “Main Street America.” They were the people who knitted together the small economic communities that once dotted this country.

In 1975, Republican President Gerald Ford and a Congress in which both houses were controlled by Democrats passed and signed legislation that did away with the Miller-Tydings and McGuire Acts, which had created and sustained fair trade laws. As chronicled by Matthew Stoller in his book Goliath: The 100-Year War between Monopoly Power and Democracy, this was the result of intense lobbying by large corporations. Almost a half century later, the results of this social experiment are in. Those results are decimated local retailers who cannot possibly compete with Walmart or Amazon, and therefore cannot own retail assets. The result is a world in which Main Street is gone.

It is time, finally, to bring back the fair trade laws.

Conclusion

Inflation is rapidly eroding the value of the assets that regular people own and making it harder for those who do not own assets to get their hands on them in the first place. This is happening on top of thirty to forty years of middle class erosion. Democracies that lose their middle class are unstable, unhappy, and divided. Most do not remain as democracies.

Americans on both the left and the right are fond of pointing to “threats to democracy.” The loss of the middle class is surely one of the greatest threats. It is time for Congress to take it much more seriously.

Tim Reichert is an economist and candidate for US Congress in Colorado’s 7th congressional district.