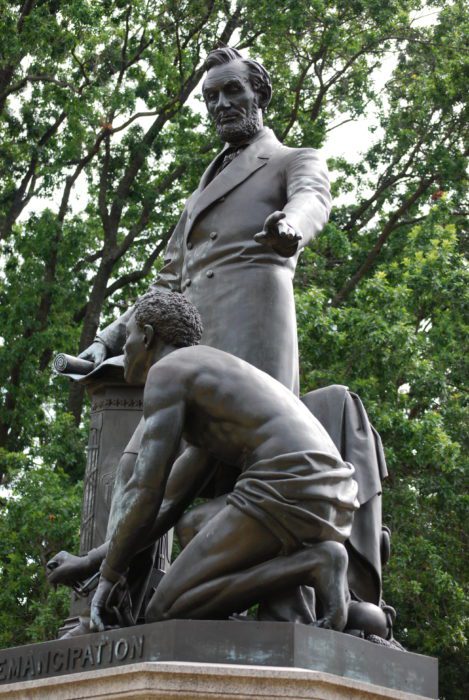

All through the Juneteenth getaway weekend celebrating the abolition of slavery, I drove across our nation’s funds for a glimpse at the Emancipation Memorial, a monument consisting of two life-measurement figures, Abraham Lincoln and a freshly freed slave. The function of the Yankee sculptor Thomas Ball (1819-1911), the memorial—also acknowledged as the Freedman’s Memorial—was mounted in Washington’s roomy, 7-acre Lincoln Park in 1876. The bronze statuary was paid out for by donations from African-Individuals, mostly soldiers who experienced served in the Union military. The funding campaign originated, nonetheless, with a previous slave, Charlotte Scott, who had been emancipated when her Unionist operator moved from Virginia to Ohio in the course of the Civil War. Congress foot the invoice for the 10-foot-tall granite pedestal, which Ball did not layout.

Catesby Leigh

Deeply moved by the news of the president’s dying, Scott desired a Lincoln monument, and that’s what Washington, DC bought. But Frederick Douglass, who delivered a lengthy oration at its unveiling—the wire having been pulled by President Ulysses S. Grant—expressed critical misgivings about the freedman’s pose in a letter to a newspaper only days later, describing him as “couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal.” There’s no debating the subordinate placement of the crouching freedman, more than whom a standing Lincoln looms. And it is hardly stunning that phone calls for the monument’s elimination proliferated at the time of the George Floyd protests. Presented the intensity of the civil problem, the statuary’s toppling was a authentic risk. The Nationwide Park Services, which is responsible for preserving Lincoln Park, erected a fence all around the monument during the protests.

The elimination marketing campaign failed—in Washington. But a duplicate of the Emancipation Memorial erected in Boston in 1879 was banished from its Park Sq. web-site.

My fascination in the Emancipation Memorial was piqued by commentaries in its protection by two Ivy League historians, Allen G. Guelzo of Princeton and James Hankins of Harvard, that appeared in the Wall Avenue Journal and New Criterion. The Journal piece appeared in June 2020, when the protests had been likely entire steam it is an abbreviated edition of the New Criterion essay that ran later in the yr. It struck me that the professors have been completely appropriate to advocate the Lincoln Park monument’s retention, but critically mistaken in their reasoning. My Juneteenth take a look at strengthened that summary. At minimum I can report that I didn’t come upon any angry demonstrators or any protective fencing. Just bicyclists, sunbathers lolling in the considerable grass, and mom and dad and young children at a playground in just one corner of the park. The monument bears some graffiti, but it genuinely wasn’t getting considerably focus. The point stays that it has been a familiar Washington landmark ever considering that its unveiling.

The Guelzo-Hankins commentary might direct a single to imagine that the Emancipation Memorial fulfills latter-working day standards for iconographic appropriateness in the remedy of its concept, insofar as the freedman is endowed with “agency.” The trouble is that the professors rather significantly misrepresent its iconography. This matters far more than a single may well feel. Obvious pondering about our monumental heritage is poorly required just before the upcoming iconoclastic rampage erupts.

Credit score: Courtesy of the Colby College or university Museum of Art

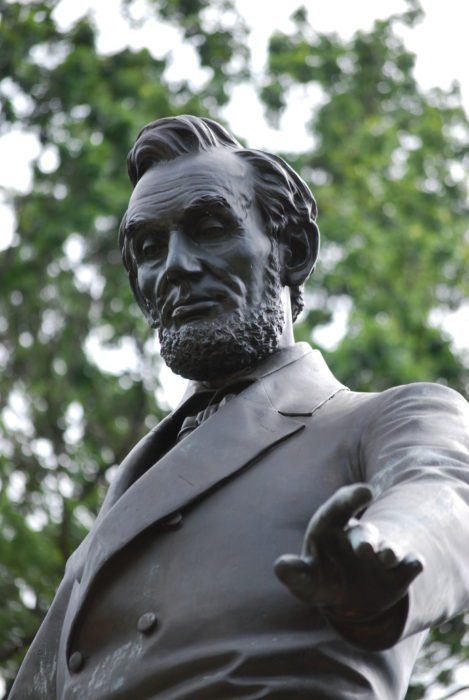

Guelzo and Hankins explain to us Lincoln “steps back” from the semi-nude freedman kneeling in front of him “as while to make room” for his rise to a standing posture. More together in the New Criterion essay they say, “Lincoln seems to stand back again with a person foot, as although in mingled amazement and appreciation of this new apparition, a free of charge black male.” Lincoln in truth appears to be to be performing no these thing, and “the mingled amazement and appreciation” are another figment of the professors’ creativeness. Lincoln’s visage assignments authority and determination. There is no recommendation whatsoever of something other than a static stance on his section, especially as one of his toes abuts a pedestal on which reside a e book and a scroll, the latter standing for the Emancipation Proclamation. For a Florence-primarily based sculptor who imbibed the neoclassicism of his era, a backward step would have been totally alien to the historical standing-statesman genre to which Lincoln naturally belongs, his frock coat and other modern-day apparel notwithstanding. The professors’ error possibly arises from the reality that, in profile, Lincoln’s torso arches back somewhat from his trunk. But the curvature of the backbone takes place to be an elementary actuality of human anatomy.

Guelzo and Hankins also notify us that “Lincoln’s still left arm is held out in a welcoming gesture, as while to clasp the younger person by the shoulder as he rises.” Also untrue. That gesture is unchanged from Ball’s authentic design for the two figures, executed at half-existence-size scale a ten years ahead of the Lincoln Park monument’s generation. In that earlier edition, the professors convey to us, Lincoln appears to be “casting some kind of spell” above a nonetheless extra youthful freedman, provided the latter’s “passive, nearly dreamlike state.” To choose by the forged of the 1865 bronze in the Colby College or university Museum of Artwork, that is not legitimate both, as we will see. In any circumstance, this freedman was replaced, in the Lincoln Park monument, with a more mature and imposing determine whose head was modeled just after a photograph of Archibald Alexander, a onetime fugitive slave. But in both statuary variations, Lincoln’s extended remaining hand is modeled with the forefinger separated from the other people, a classical method of articulating the hand that, in this context, is certainly meant to convey the concept of authority or electricity. Alexander is the beneficiary of Lincoln’s benevolent workout of his business.

Guelzo and Hankins be aware that when the monument is viewed “from below” Alexander seems to be more substantial than Lincoln. They erroneously attribute this result to “foreshortening,” a pictorial approach in which forms lying in a airplane that is not perpendicular to the spectator’s line of sight are abbreviated in purchase to develop a reasonable perception of depth in perspective. But at minimum the optical illusion the professors take note is true. It is also of minimal import. When we glance up at the two figures from beneath the major impression is of Lincoln looming in excess of Alexander. This is, yet again, a Lincoln monument. Lincoln is fully noticeable each from the entrance and the rear of the monument. From the rear, Alexander is largely screened by the stump of a whipping submit with a floral vine increasing on it and drapery solid over it, as nicely as by Lincoln himself. It issues, of study course, that Alexander has a extra effective presence than his predecessor in Ball’s half-existence-dimensions edition. But to suggest that the actuality Alexander would be as tall as Lincoln if standing up “form[s] a visible correlative to the new point out of legal equality concerning the two men” is to inflate, preposterously, the importance of a trivia-quiz factoid.

The 1865 bronze is a instead curious do the job. In that edition, the younger freedman sporting activities the Phrygian cap of emancipation. His pose is closely akin to Alexander’s—leaning ahead in the crouching placement, with the fingers of his left hand resting on the ground. As for his “passive, practically dreamlike condition,” his gaze is in simple fact directed to the Union defend that Lincoln is holding. That defend is perched over 4 stacked textbooks and, on prime of them, the partially unwound scroll bearing the Proclamation. (There is no pedestal in this before bronze.) The undeniable oddity is that the young freedman is seeking at the shield’s concave interior with its grip, not the convex exterior bearing stars and stripes. Lincoln’s suitable hand clasps not only the defend, but also a victory wreath pressed towards its exterior. Nevertheless rendered a lot less intelligible by the shield’s orientation, the meant concept looks to be that Lincoln is inviting the freedman to ponder the colossal martial exertion that, less than the martyred president’s command, introduced about his liberation. In addition to his gaze, the stylized articulation of the fingers of the freedman’s ideal hand suggests contemplation. He is certainly not “rubbing” his still left arm where it was just lately shackled, as the professors assert. His still left wrist continue to bears a shackle in the Colby bronze.

In the final model, Lincoln’s correct arm rests on the Proclamation scroll and a reserve, the pedestal beneath them currently being decorated with the Roman fasces symbolizing republican authority, a Union protect bearing 13 stars (for the reincorporated Confederate states), and a portrait bust of George Washington in relief. Alexander, who wears no cap, is somewhat reoriented relative to his more youthful predecessor, who was aligned so as to be seeking at the shield. Alexander is situated perpendicular to Lincoln so as to peer out into the distance. He is a more partaking determine than Lincoln, whose modeling leaves something to be sought after. We get much too very little perception of the animating type less than the latter’s vesture, which pretty much appears as if it were garments a mannikin. If the muscular freedman is not increasing to his feet—the spectator’s choose on this depends on the angle of vision—he is definitely about to. But his higher remaining leg (the still left leg being the extra seen just one) is even now pushing down on the calf, not soaring from it. Alexander’s most definite muscular action is in his correct arm, elevated somewhat above his right thigh, with the hand locking a sundered shackle in its grip. The freedman is having stock of his new beginning as a citizen.

The Guelzo-Hankins New Criterion essay tells an critical story about how the Emancipation Memorial arrived to be. The professors are unquestionably right when they argue that deciphering it as a monument to white supremacy quantities to caricature. Their iconographic misinterpretation, even so, obscures an essential part of general public monuments’ function: as landmarks indicating where we have stood as a political and cultural neighborhood about the study course of our background. Presently, a monument to Lincoln or emancipation would not be conceived in the Emancipation Memorial’s explicitly hierarchical terms. And the professors would have done nicely to deal with that challenge rather of burying it beneath a pile of wishful contemplating.

Through, and after, the Floyd protests we noticed more than enough, and massively extra than enough, of the purgation of American civic art—largely as a consequence of fanaticism or cowardice—that can only serve to degrade the nation’s community realm. And, as I said out the outset, other iconoclastic rampages carried out by barbarians who feel they have a monopoly on truth and justice just about surely lie in our future. That is why it is of very important great importance to occur to phrases with our monumental heritage in all its complexity and polyvalence—to make positive the vandals never catch us unawares subsequent time all over.

Catesby Leigh is The American Conservative’s New Urbanism Fellow. He writes about public artwork and architecture and lives in Washington, D.C.This New Urbanism collection is supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Basis. Follow New Urbs on Twitter for a feed dedicated to TAC’s coverage of towns, urbanism, and position.